How To Think in a Second Language

I was so excited to read a recent NYT article “Do We Need Language to Think?” by @Carl Zimmer because not only does it explain how our thoughts and words connect, it also verifies how I experience “thinking” in a second language.

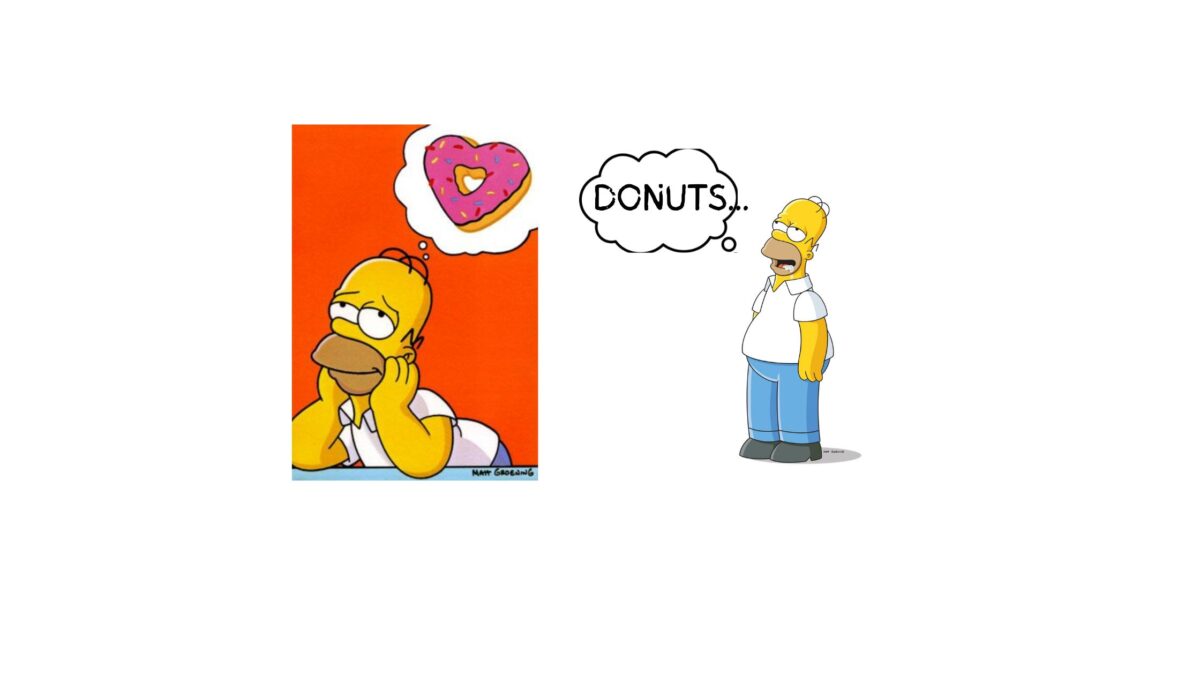

So, what is the connection between thoughts and words exactly? Let’s take our friend Homer here. For him it is not the combination of the letters d-o-n-u-t that comes first and causes him to salivate, but the image, the concept of “donut,” that springs to mind. First the thought, then the words.

We all have “donut” moments in which we find ourselves unable to come up with the words to express something: an undefined feeling, the name of a famous person. This suspended, wordless state–when we take hold of an idea or concept but have not yet formulated the words to express it–is what we want to capture when we are in our second language. The challenge is that, when we “think” –form mental concepts–our native language clicks into gear and produces words so quickly around our thoughts that the distance between the thought and the words is imperceptible. So much so that we might not be aware that our words and thoughts are not one and the same.

Having studied six languages, I have, over decades, trained my mind to slow down so I can experience my thoughts before they become articulated. In fact, I’ve gotten so good at this that I often have difficulty putting my thoughts into verbal focus in English! I literally draw out the process, try to free my mind of words, and stay with the feeling or image I have in my mind. Holding this “thought”, I draw from the language track in which I am operating. I, then, access my toolbox in that language and use whatever vocabulary and grammatical glue I have available to get my point across. In my weaker languages, I clumsily cobble something together. In my stronger languages, I can almost sound like a native speaker. In both cases, when my English tries to creep in, I swat it away like an annoying fly.

That said, when operating in your new second language, like most, you will find that the words in your native tongue come flooding in and insert themselves to bring verbal expression to your thoughts. Indeed, there is nothing wrong with quickly coming up with an articulation of your thoughts in a language you are at home with. In fact, it is quite natural. The trick is to recognize this moment and try to fight the temptation to just say it in, say, English, because it’s “easier”. On the contrary, you have now given yourself the difficult task of translating those fancy sentences into your new baby language.

Ultimately, the trick is to understand that those native language words that are coming in are not your thoughts. They are your native language elbowing out your new language’s direct access to your thoughts. In our new language, we are like a toddler working to develop verbal skills. This part of our brain simply can’t compete with the speed and agility of the adult language skills we have spent decades honing. Over time you can teach your mind to let go and allow your new language to connect directly with your thoughts and come up with a way to communicate. It will be halting, inaccurate and slow at first. And so what?! Use what you’ve got to Macgyver sentences together. As long as you are able to communicate, you are winning and, more importantly, with each attempt, you will feel more at ease, get better and and stronger.

Start with the “donut” and see what you can muster up in your new language to describe Homer’s thought. And while you’ll likely not end up with “He’s thinking about donuts which transport him to a blissful, nirvana-like state of sweet, fried deliciousness” coming up with “he think about good pastry” while perhaps not the most poetic articulation, will do just fine.

By Elizabeth Zackheim, co-founder of ABC Languages